Imagine your UI and end-to-end tests could run an order of magnitude faster than they are now? Oh, you don’t have end-to-end tests, because they would be too slow and brittle? I have had that too, don’t worry. Imagine then if you could have cost-effective end-to-end tests. How would that impact your product development?

Fast browser tests in addition to…

As Marc and Rob have described in their series on architecting and test-driving Vue.js (see How to keep Front End complexity in check with Hexagonal Architecture and A Hexagonal Vue.js front-end, by example), we like to have tests in our front-ends, for anything that can possibly break. In addition to that, I like to have:

- at least a set of end-to-end tests to check few main scenarios;

- a playground for components we made or just use;

- a type system to make sure everything still hangs together, leaving time to focus on tests for interesting behaviour.

My go to tool for browser and end-to-end tests has been Selenium, at least for the last ten years. I make a distinction between browser tests and end-to-end tests, because if you can easily test visual components fast and in isolation, it becomes attractive to do that as well.

Selenium is battle tested, but it has several moving parts and does not execute particularly fast. So I tend to automate only a few scenarios, and leave the rest to non-visual unit tests. I also tend to delay writing Selenium tests until the application is further fleshed out. The risk that I had materialize, is that we have structured our application and the services it uses in such a way that adding browser tests has become time consuming or nigh-on impossible.

Shortcomings of non-visual tests for a front-end

Interpreting the result of the unit tests in the UI costs mental energy: you have to make the mapping between what the tests tell you, and how it looks on the screen in your imagination. For instance: it is useful to know that a specific validation failure will disable submitting on a forms model, but what does it look like?

I’m quite handy at writing unit tests, so my UI is usually not broken, and the tests pass. When the tests pass, I push a small feature to production and move on to the next part. However, that means that I tend not to look at the UI enough. If there are clumsy interaction patterns, I will not notice them.

I was one of those people who would go: “My tests are great, now I don’t have to click through the UI all the time”. When I hear something like that now, I cringe. Although it is preferable to observe actual users, they are not always available when I need to work on an application. I knew in theory that using the application yourself is a powerful feedback mechanism: exploratory testing.

To explore an application, you need to do two things:

- get to the area in the application in that you want to explore

- get the application in an interesting state Yet some states are hard to achieve in a test situation, and doing this in production is not necessarily feasible. So when after a long time, I am finally brave enough to click through the UI, I go “Oh. this is … bad!”. And because it is slow and cumbersome, I cannot immediately fix it, and the pattern repeats.

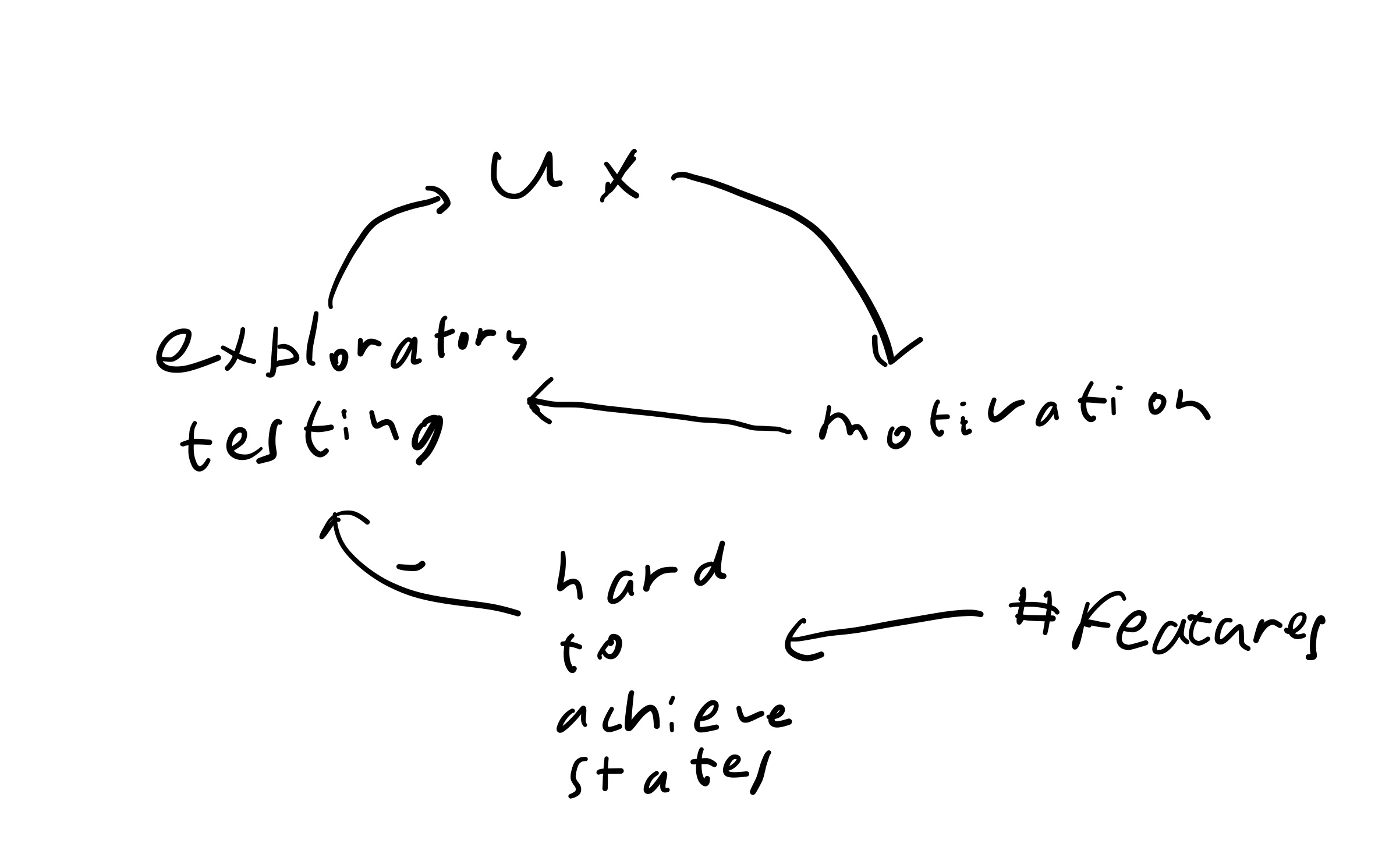

A quick diagram of effects illustrates our predicament:

The optimistic loop is: exploratory testing leads to better UX, which in turn leads to more motivation. When we are motivated, we do more exploratory testing, etc. This is limited by the time we have available and by hard to achieve states. The more features we have, the more hard to achieve states we have, the fewer exploratory tests we can do.

The optimistic loop is: exploratory testing leads to better UX, which in turn leads to more motivation. When we are motivated, we do more exploratory testing, etc. This is limited by the time we have available and by hard to achieve states. The more features we have, the more hard to achieve states we have, the fewer exploratory tests we can do.

We can do more exploratory tests by sheer force of will, or throwing more people at the problem. But if everything is manual, this is expensive and it doesn’t scale. The time elapsed from an incoming user issue to first reproduction remains high, especially if it is a part of the UI we haven’t worked on in a while.

Selenium works, but is tiring

Selenium helps me to see the UI in action, but watching it run the tests, including browsers spawning etc. is tiring. So in effect I use it similarly to unit tests. I look at the UI I am developing and when a test fails, but not otherwise, because the threshold is too high.

What if we made our system fast?

End-to-end tests can be fast, if you design the front-end and back-end system(s) for fast test runs. I have done this, but in existing systems that option is not always available. Rather it is something we have to work towards. This is an area where a modular browser testing tool like Cypress can come in handy.

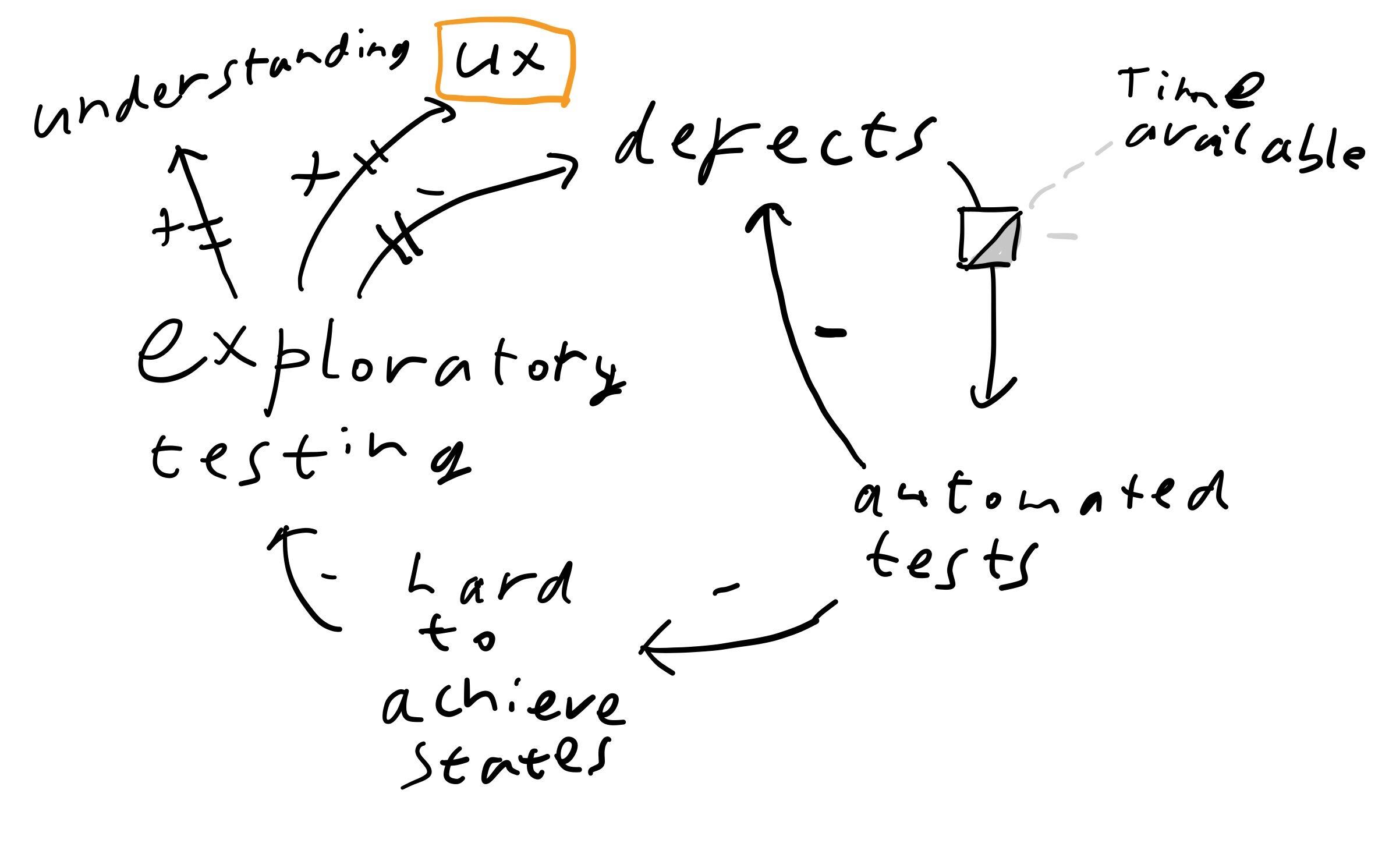

I’ve made another diagram of effects to illustrate what happens when it is easy to set up an exploratory test.

Casting a wider net of automated tests leads to fewer hard to achieve states. When we have fewer hard to achieve states, we can devote more time to exploratory testing, which means we have fewer defects, and more time available to do automated tests, and then we have come full circle, with fewer hard to achieve states.

Casting a wider net of automated tests leads to fewer hard to achieve states. When we have fewer hard to achieve states, we can devote more time to exploratory testing, which means we have fewer defects, and more time available to do automated tests, and then we have come full circle, with fewer hard to achieve states.

Marc suggested, rightly, that exploratory testing doesn’t immediately lead to fewer defects. So I’ve drawn a delay there. Working through an application, even when the parts run fast, takes time. Understanding and better UX also take time.

Why Cypress

What is powerful about Cypress, is that it lives in the same environment as the SPA front-end. Same language, same toolchain, same people. Working test-first, without hand-offs and waiting was a game changer for unit tests, and now with Cypress it can be the same for UI tests and end-to-end tests as well.

Cypress makes it easy to separate end-to-end tests and UI tests. Since the tests are white-box and the test-code inhabits the same space as the UI code, it is easier to isolate small bits of the UI and test them visually, quickly. Cypress offers support code to start where you are, possibly with end-to-end tests, and stub out dependencies as you go.

If you start fresh, Cypress lowers the bar for developing with hexagons and using the Humble Dialog pattern instead of a tightly coupled network.

Changing the speed at which something runs by an order of magnitude is a game changer. I’ve experienced this with test driven development at the unit level in the past, and once with Selenium (after architecting the application to be fast).

In order to give you an impression of the speed, I made a small video, generated by cypress run. The commentary is mine, the video was made without any additional work, this comes out of the box.

You can always slow down fast tests if you need, the other way around is much more difficult.

Further reading

Marc and Rob recently wrote about How to decide on an architecture for Automated Tests.

Explore it by Elizabeth Hendrickson

Yves Reynhout recommended Test Cafe on twitter for his use case:

I've switched to testcafe since cypress didn't deal very well with navigating to other domains (e.g. brokered authentication). While the argument is that it's not part of the SUT, I found that changing / special casing the SUT to be able to cope with it just not worth my time.

— Yves Reynhout (@yreynhout) October 1, 2020

Thanks to Marc and Rob for encouragement and careful questioning.