In this post, we will share another benefit of looking through the Hexagonal Architecture lens: it supports making decisions about the architecture of automated tests in your application landscape. It can guide you in questions like:

- What kinds of tests cover which concerns and which risks?

- What mix of automated tests is appropriate for my context?

- What mix of tests will provide confidence that my changes are ready for delivery?

- How can I move a test within my test architecture to get faster, more specific feedback?

We have introduced our view on Hexagonal Architecture in previous posts: hexagonal architecture and How to keep Front End complexity in check with Hexagonal Architecture.

An example application landscape

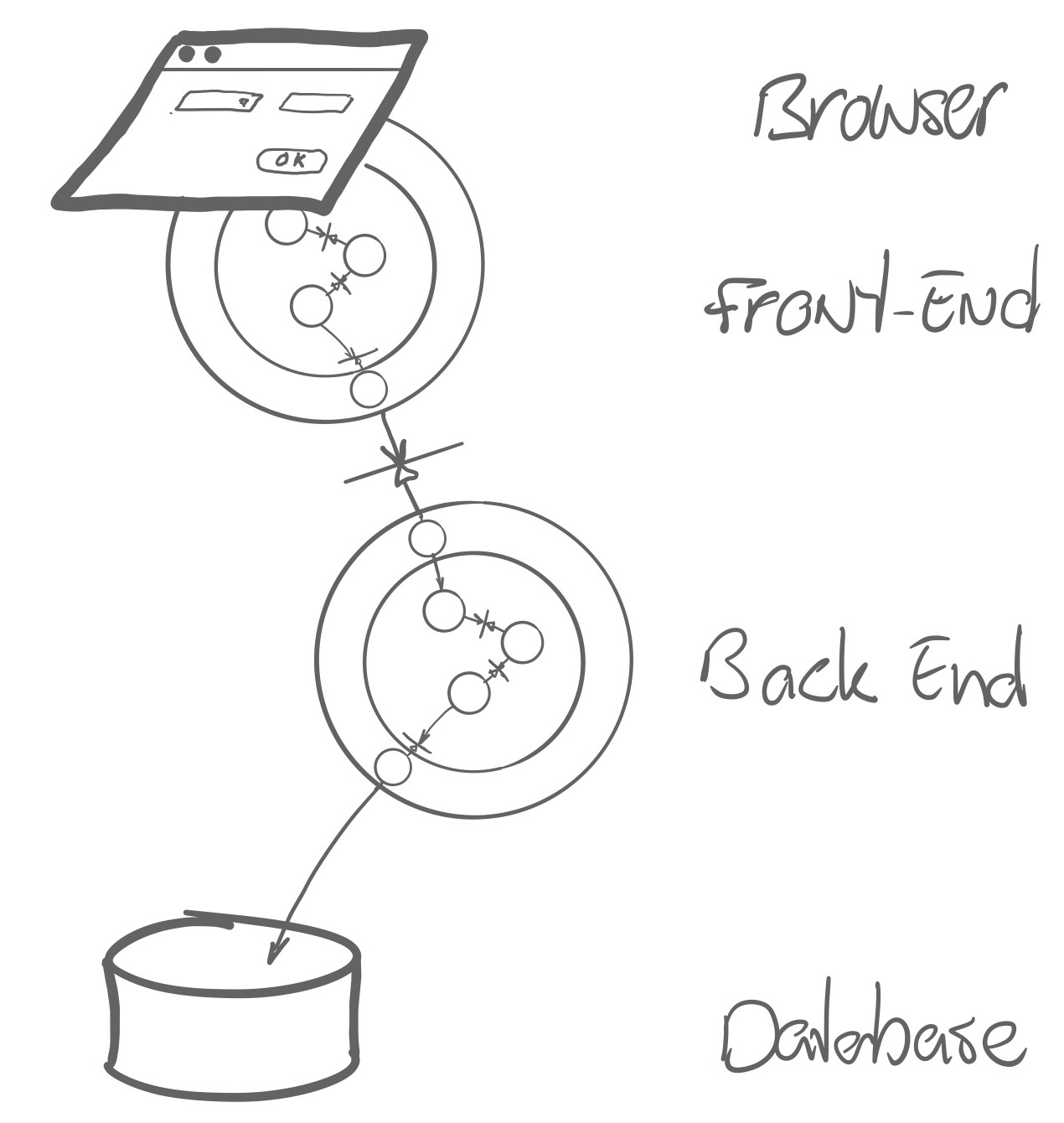

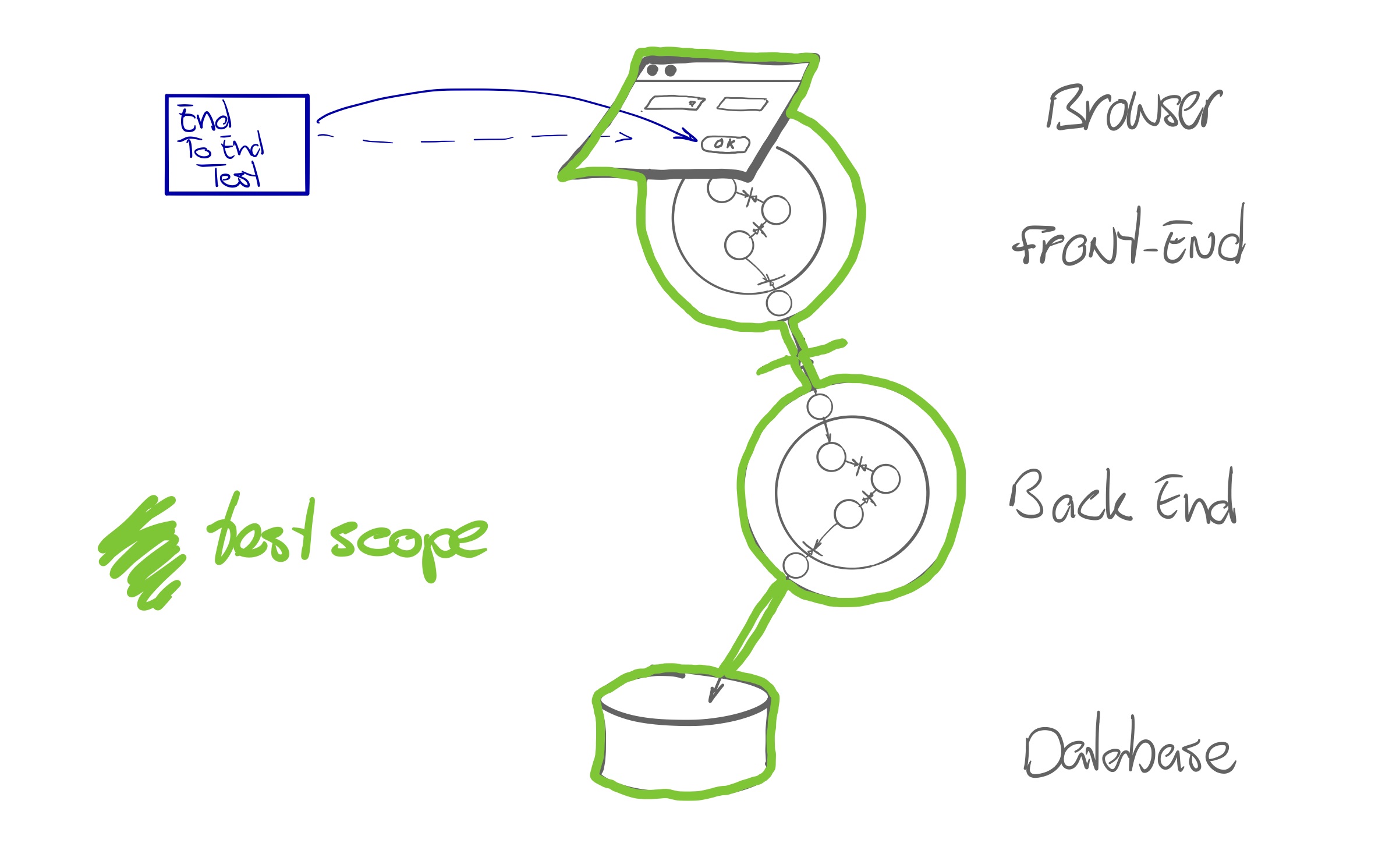

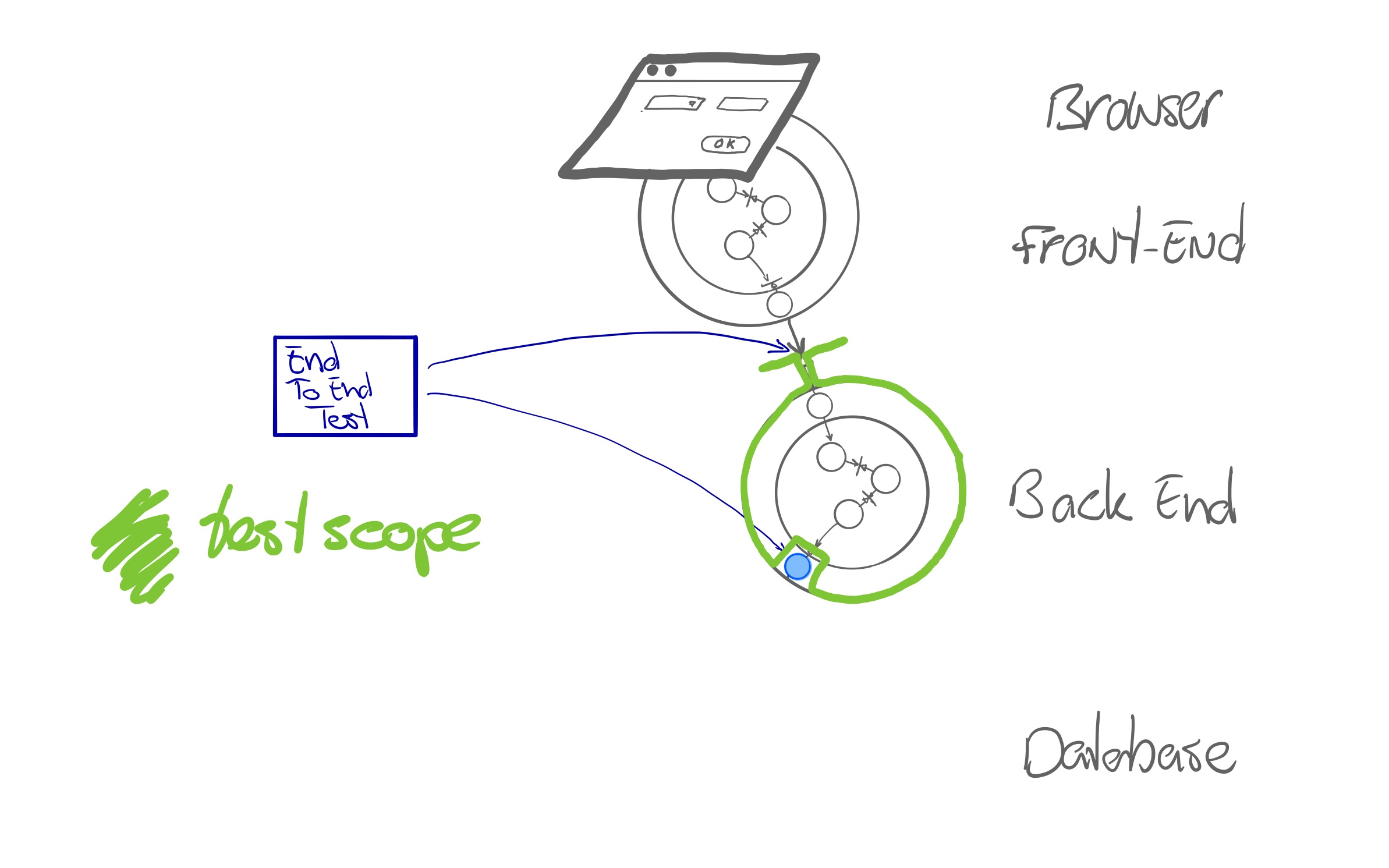

Say we have an application that consists of a backend component using a database, and a frontend component running in a web browser. The backend exposes an API, which is represented by the perpendicular line between frontend and backend in the picture below.

We see both the frontend and the backend as hexagons, each with its own domain, its own ports and its own adapters. The business logic and view logic is in the center, dependencies go outside-in.

Automated tests

Looking at our application landscape in this way, we can define different types of tests having different scopes:

- unit tests

- adapter integration tests

- contract tests

- end to end tests

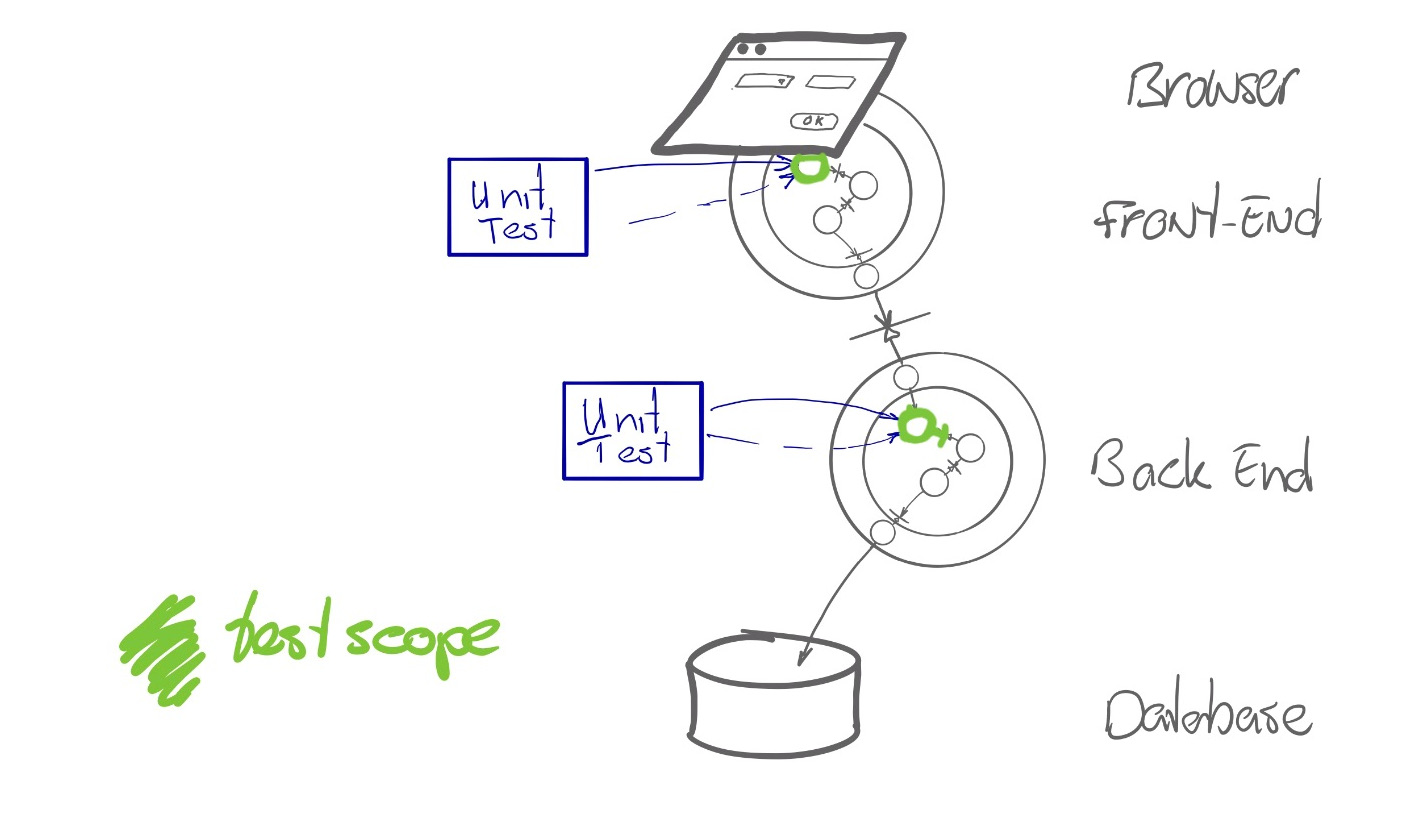

Unit tests

The term unit test is often used for any automated test written by a developer, but we prefer to stay close to its actual meaning: an automated test for a unit, i.e. one object or function, or a small cluster of objects.

We write Unit Tests for the domain logic inside the hexagons. Because the domain does not depend on outside stuff, we can test it in isolation and write clear tests that speak the domain language.

Unit tests for a component have a limited scope and run fast, in milliseconds. A whole suite should run in mere seconds.

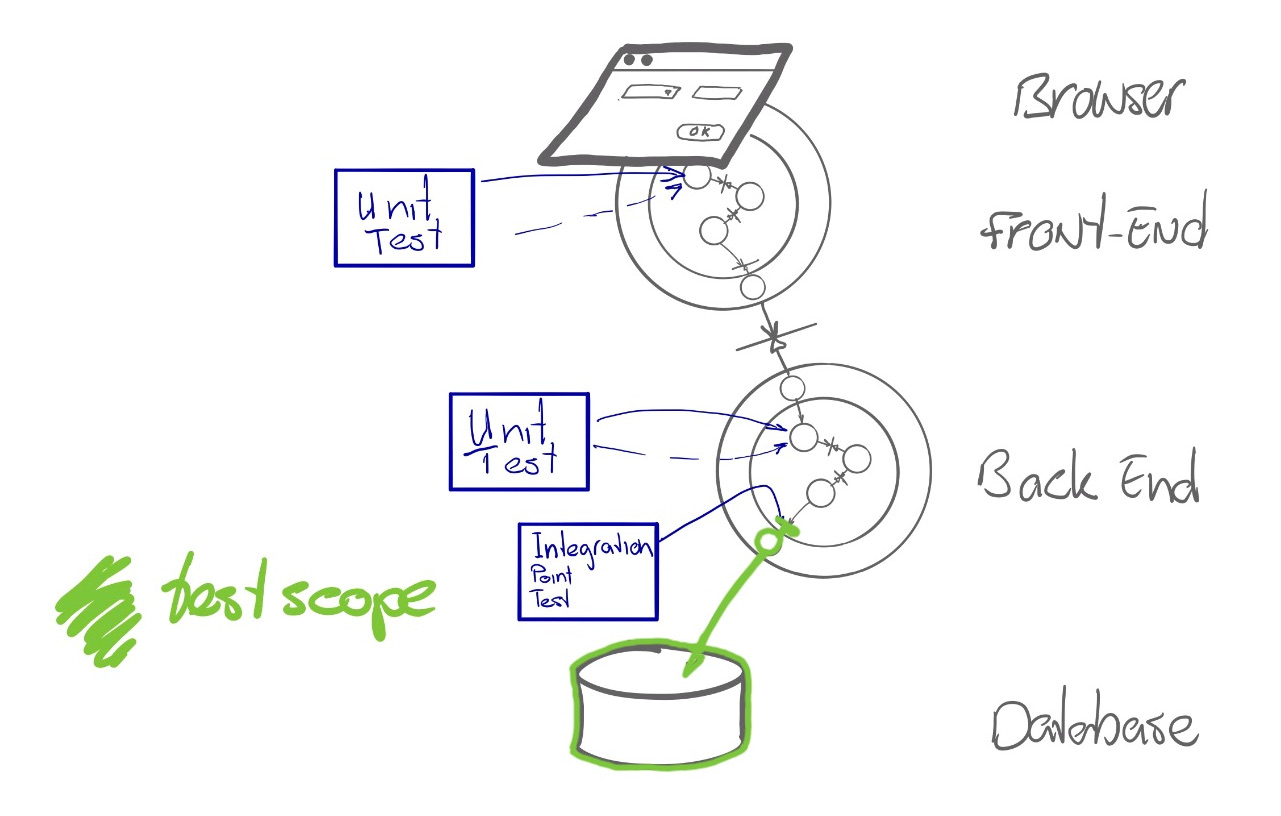

Adapter integration tests

By decoupling adapters from the domain, we can write focused automated tests for adapter concerns. In the Growing Object Oriented Software Guided by Tests book, these tests are called Integration Tests. We prefer Adapter Integration Tests or Integration Point Tests, to express the intent a bit better.

Adapter Integration Tests verify whether an adapter integrates properly with a database, an external API, etc. The test exercises the adapter mainly through its domain interface.

In the backend component of the Agile Fluency® Diagnostic application we’re working on, we have a Facilitator Repository that stores data about facilitators in an SQLite database. It provides a domain oriented interface with functions like save and all, to save a facilitator and to retrieve all facilitators. It looks like this in Python:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

class DBFacilitatorRepository:

def all(self):

return map(as_facilitator, FacilitatorRecord.query.all())

def save(self, facilitator):

record = FacilitatorRecord(...)

db.session.add(record)

db.session.commit()

def as_facilitator(record):

return Facilitator(...)

...

This adapter integrates with the database library and takes care of mapping domain objects to and from database records.

The adapter integration test sets up an in-memory SQLite database, creates the database schema, runs migrations, and then runs the test via the domain interface. The scope of the test include database integration and mapping to and from domain objects, which is typical for adapter integration tests.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

class TestDbFacilitatorRepository:

class TestConfig(object):

SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI = 'sqlite:///:memory:'

@pytest.fixture(autouse=True)

def setupDb(self):

the_app = create_app(self.TestConfig)

with the_app.app_context():

self.repo = DBFacilitatorRepository()

db.create_all()

yield

def test_creating_a_facilitator_makes_it_available_in_the_repo(self):

facilitator = aValidFacilitator()

self.repo.save(facilitator=facilitator)

assert list(self.repo.all()) == [ facilitator ]

...

We can choose how much of the integration we want to cover in the test: our

TestDbFacilitatorRepositorytest could also use a real database running on our local machine and in the build environment, to make the difference with the production situation even smaller.

For sending emails, we have written an adapter integration test that checks our SMTPBasedMessageEngine with a fake SMTP server that we start and stop from the test. Alternatively, we could test with a real SMTP server and poll a test mailbox for messages. Although closer to the actual production situation, this approach is slower and more brittle - again a trade-off.

The automated tests we write for our Vue.js based UI components are also adapter integration tests. We see UI components as adapters integrating with UI framework. Tests for UI components verify if we integrate correctly with the UI framework. Seeing UI component code as adapters helps us to move logic out of UI components: validation logic for instance is not about UI framework integration, so we rather move it to a separate domain object having its own fast unit tests.

Testing your front end application with different browsers is another example of adapter integration tests. The intent of these tests is to verify if the UI behaves correctly in different browsers. We do not want to use full-system end-to-end system tests for this, we just want to have the front end component running e.g. against stubbed backend APIs.

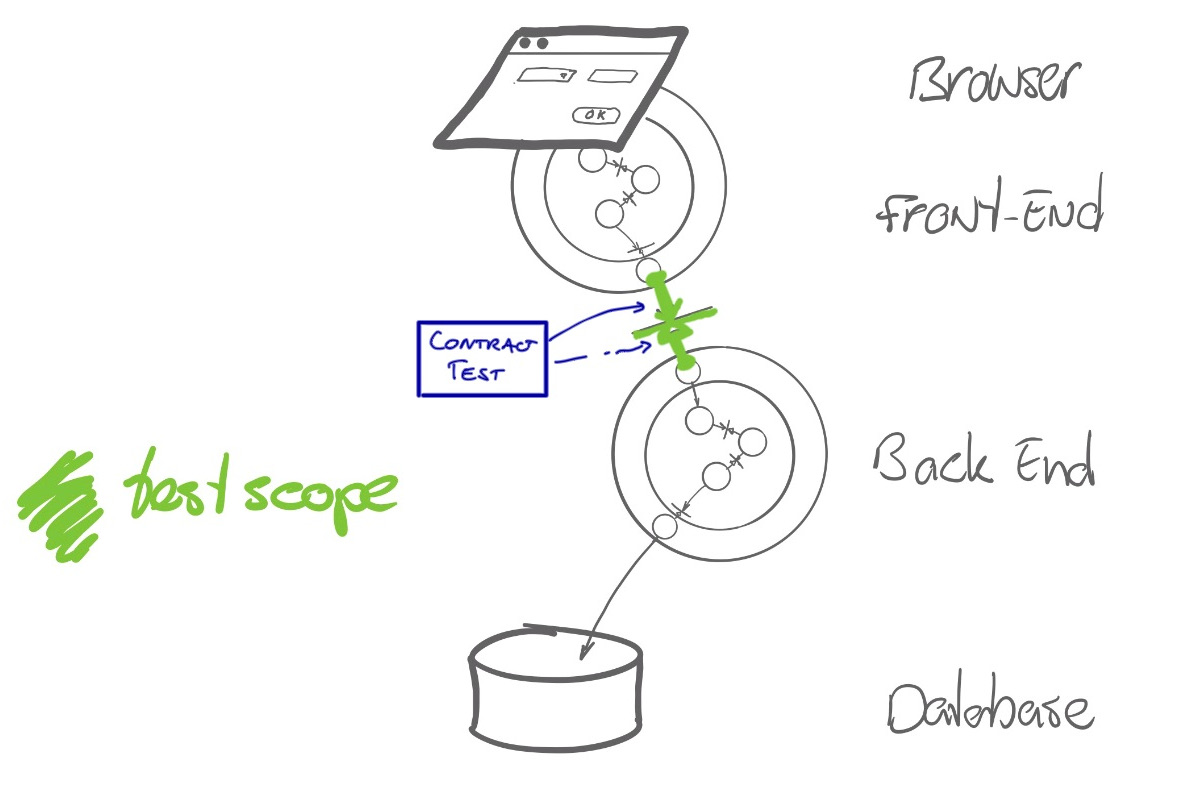

Contract tests

We can define tests around the contracts between the producers and consumers of an API. Recently, contract tests have been given a boost by Pact. Pact offers a specific way of contract testing: Consumer based contract testing.

For consumer based contract testing, all consumers of an API publish examples of how they use that API. The contract testchecks the examples against the producer implementing the API. In this way, you get quick and specific feedback if all known consumers can still work with the changes in the API.

In practice, we often see teams using end-to-end tests to catch contract related problems. Contract tests however provide better feedback faster.

Versioned schemas for API contracts are an alternative solution. Schemas make evolution of APIs a bit of a hassle (sometimes that’s a good thing, especially with public APIs). Contract testing is more flexible and supports smoother evolution, as for every API change, it checks all consumers.

End to end tests

End to end tests exercise a larger part of the application landscape, end to end. In practice, teams implement end to end tests as tests covering almost the whole application landscape through the UI running in a browser. System-wide, UI based end to end tests have a number of problems:

- a large scope and many components involved means many moving parts, and slow, fragile tests

- testing through the web browser is notoriously fragile and slow, although recent developments like Cypress make it less burdensome

- the many moving parts all behave asynchronously; handling asynchronous behaviour is a challenge and many teams are struggling with flaky tests as a result

- the feedback from the tests is not helpful; a test fails for instance complaining about a button that does not appear. What is the actual cause? Where can we find the cause? In the front end? Is it a mistake in the API? Or a mistake in a business rule buried deep in the backend?

There’s much to discuss about end to end tests. See for instance Integration Tests Are A Scam by J.B. Rainsberger. They come at a huge price. Relying on them for your confidence that your code works correctly is not very effective for the reasons mentioned above.

We prefer to focus on fast, valuable feedback and rely on unit tests and adapter integration tests rather than end to end tests. Where we do feel the need for an end to end test, we like to play with the end-to-end-ness of these tests. There is always a limit to the end-to-end-ness. When your system integrates with a third party system without a test environment, end-to-end-ness stops there. If it is simply too slow or too brittle to run automated tests against an external system, you may choose to reduce the end-to-end-ness. Striking a balance between risks and swiftness of tests is key.

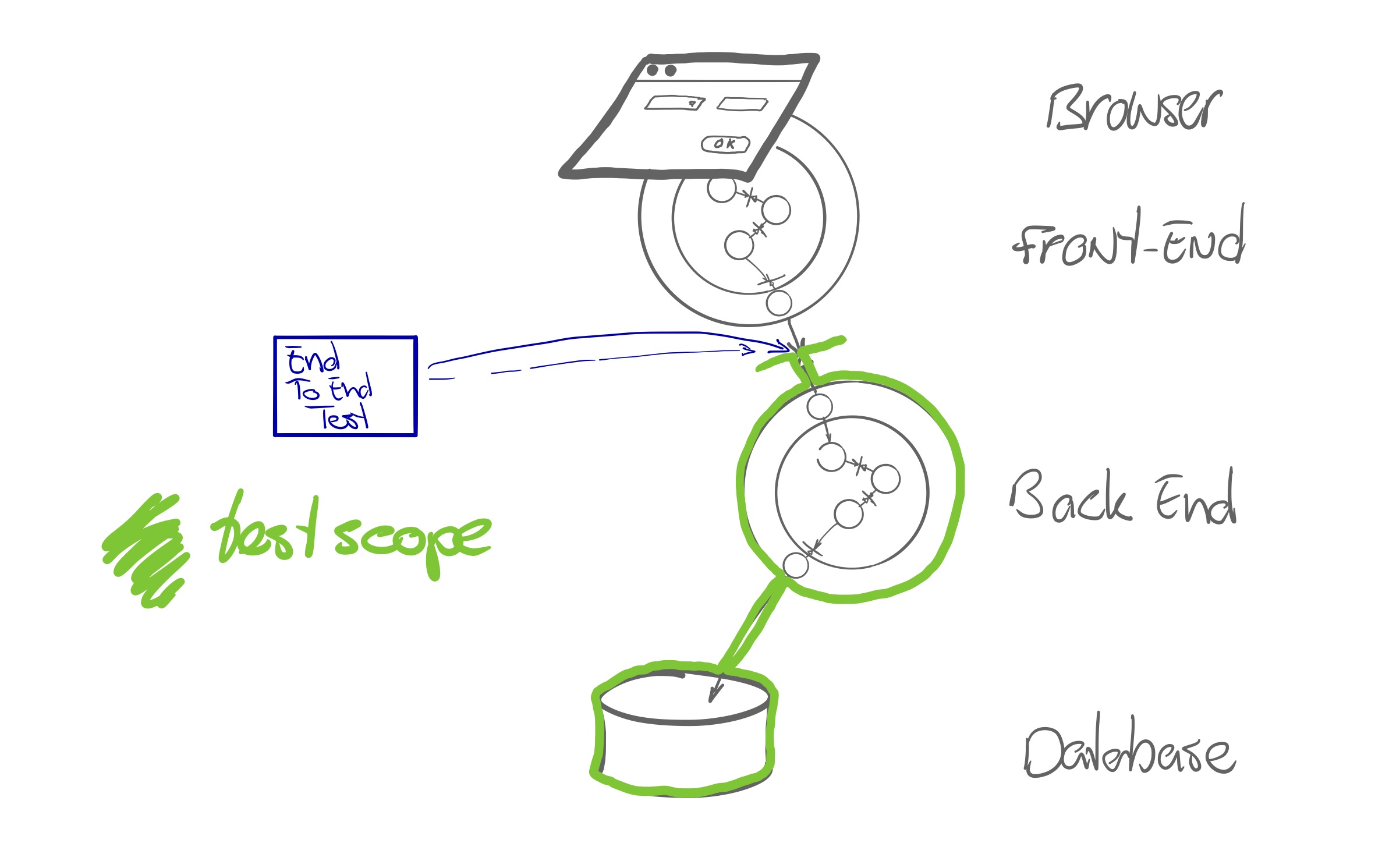

For example, we can create an end-to-end test that uses the API of a component and exercises the component with its database and possibly some other (real) components. Testing though an API is simpler and less fragile than testing through a UI.

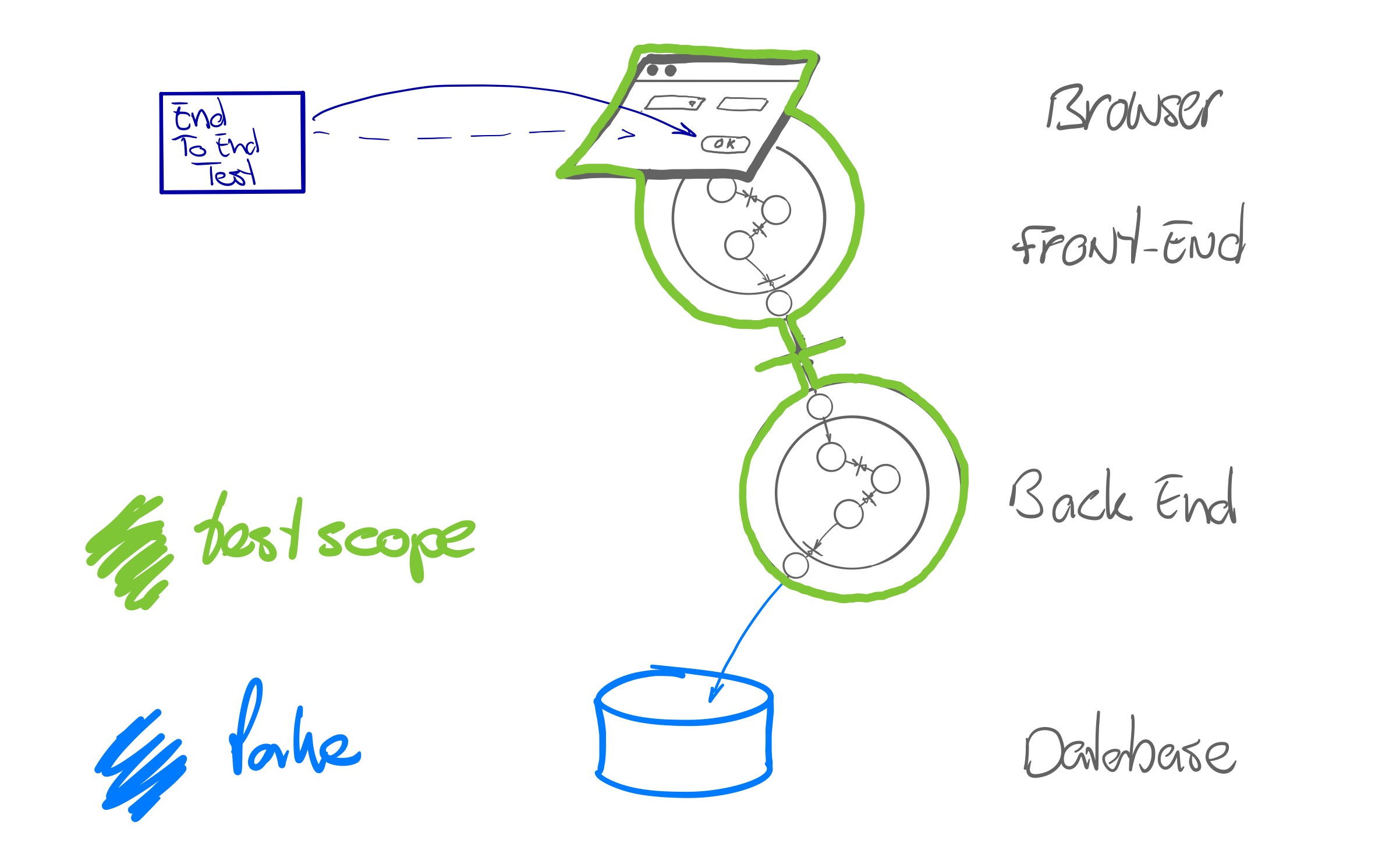

We can test end-to-end with a fake database, instead of a real database. This speeds up the test and avoids state that needs to be cleaned up.

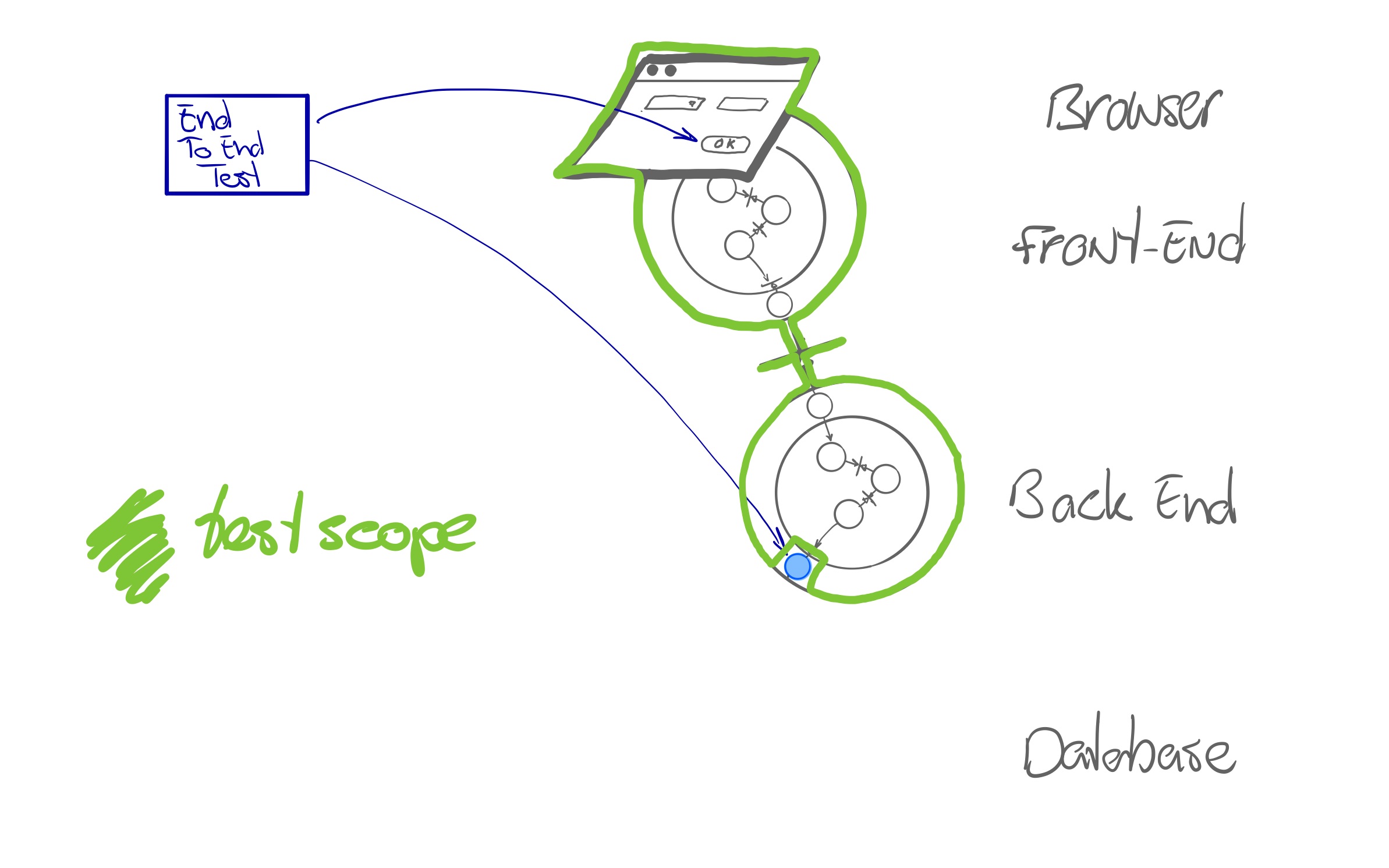

Fake databases can still be slow. If we cover database integration with Adapter Integration Tests, we can opt for wiring the component with a fake repository implementation.

We can test the backend component end to end via its API, with fake repositories. This option provides quite an effective balance between speed and end to end concerns. In one specific project we used this, as the emerging complexity of one component’s behaviour asked for more than just unit tests. Wiring the component like the picture below allowed us to run interesting scenarios at the speed of unit tests. The feedback from failures in these tests was suboptimal however, so for each failure, we discussed what unit tests were lacking.

There are many ways of creating end to end tests, with different trade-offs. A few years ago, Nat Pryce for example did a thought provoking presentation about end to end functional tests that can run in milliseconds.

Conclusion

Looking at your application landscape and your services through the Hexagonal lens provides you with useful options on how to design and structure different automated tests. It moves away from ideological debates and focuses on getting useful, fast feedback with reasonable investment.

There is no single right way or best practice for your test architecture, but we do have preferences:

- Working test driven: we test-drive our domain, our adapters and our user interface code.

- We love continuous feedback from many small, focused, fast unit tests.

- We prefer unit tests and adapter integration tests to end to end tests.

- Investing in adapter integration tests provides a high level of confidence in adapter code and reduces the need for end-to-end tests.

- Keep broadly scoped end to end tests to a minimum.

- We apply the same thinking and similar considerations - hexagonal view, unit tests, adapter integration test, end to end tests - for front end code.

- When we find an issue in an end to end test, we will analyse if the concern can be covered by a unit test (is it a domain concern?), by an adapter integration test (is it about integration or mapping?), or by a contract test (is it about components talking to each other?).

We let us guide by the feedback loops in our development process. We always look for ways to get better feedback faster.

References

- Growing Object Oriented Software guided by Tests book by Steve Freeman & Nat Pryce

- The original article on Hexagonal Architecture by Alistair Cockburn

- Alistair Cockburn presenting the history and the considerations behind Hexagonal Architecture: part 1, part 2, part 3

- Integration Tests Are A Scam by J.B. Rainsberger

- End to end functional tests that can run in milliseconds by Nat Pryce