We wrote in our previous post on coupling: without coupling there is no working software, but how do we keep coupling manageable? In this post, we will look at Hexagonal Architecture from a coupling perspective. Hexagonal Architecture is about decoupling domain logic from frameworks and the outside world - but what does decoupling actually mean?

Hexagonal Architecture recap

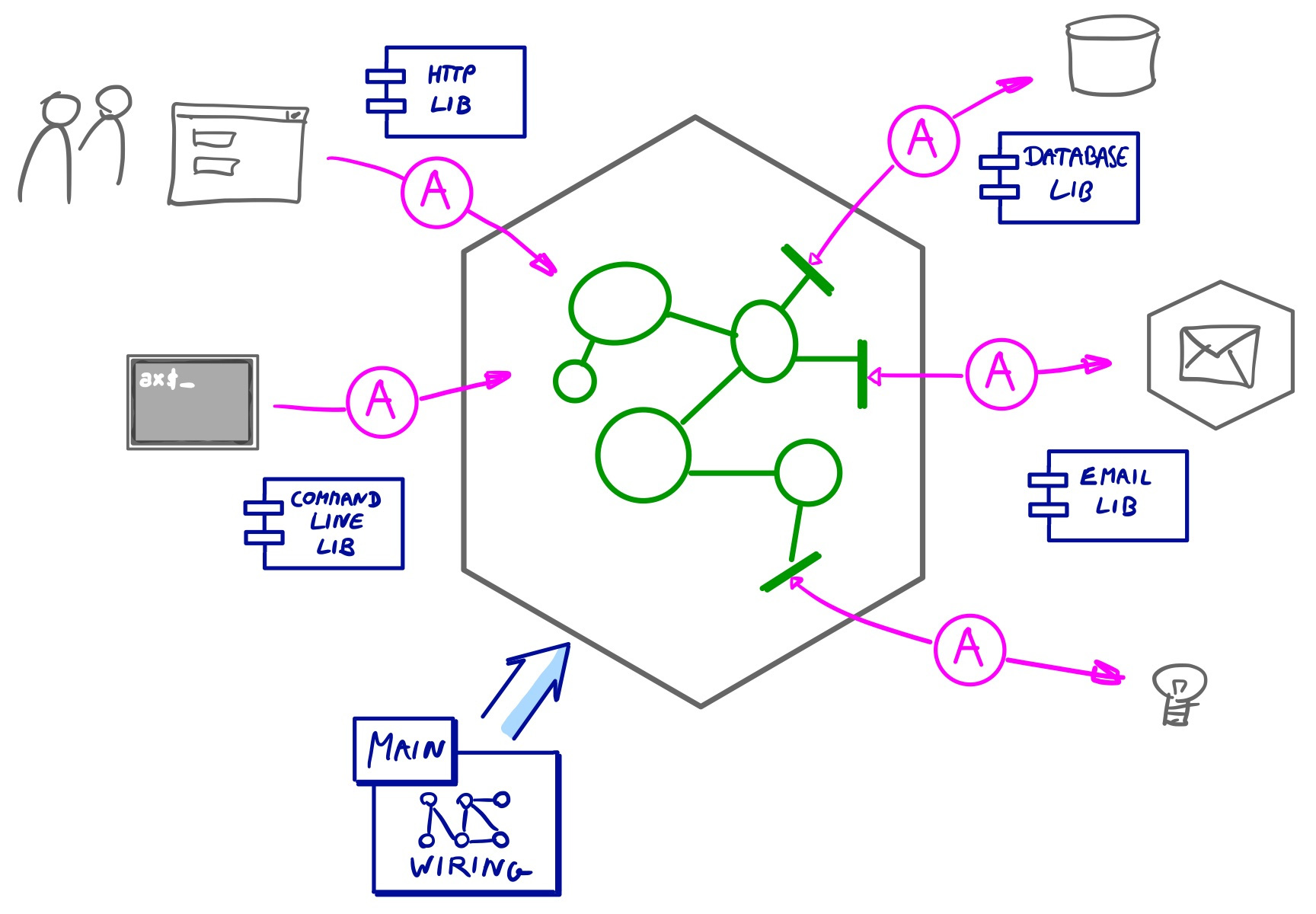

Hexagonal Architecture, also known as Ports & Adapters, is a software architecture pattern that provides guidance in structuring a component or application and managing dependencies inside the component.

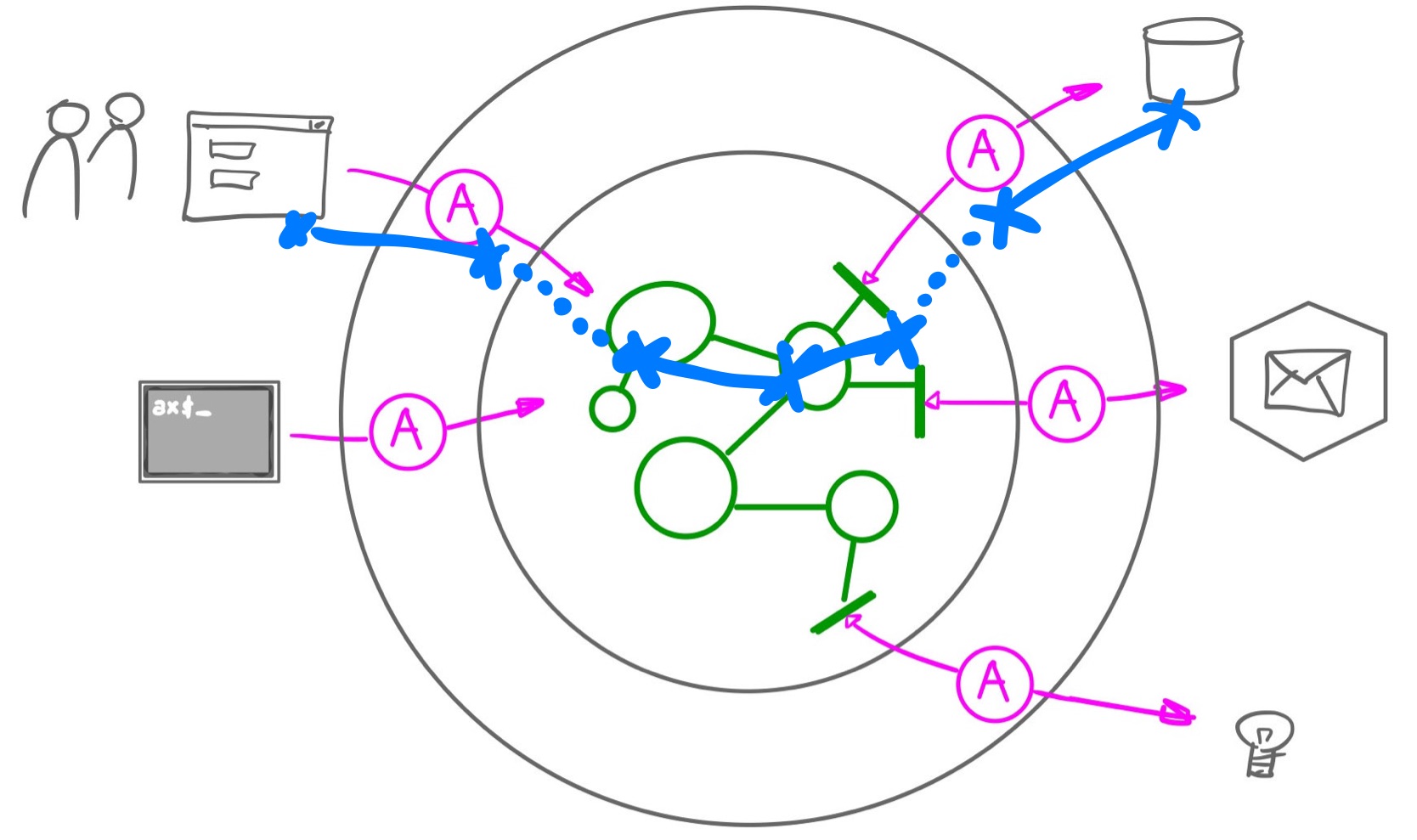

It applies the Dependency Inversion Principle at the component level: it puts the domain logic at the center, without any dependencies on databases, web, APIs. A set of interactions with the outside world with the same intent is represented by a Port. The outside world interacts with the domain logic via Adapters that map the outside world to the domain model and the other way around.

Ports can be driving (incoming) or driven (outgoing). For driven ports, adapters implement interfaces that are part of the domain model, visualized by the green thick lines in the picture below. Libraries and frameworks reside on the outside.

See our earlier posts to learn more (or book a course 😁)

Hexagonal Architecture in practice

We have applied Hexagonal Architecture in many projects. It has also been embraced by the Domain Driven Design community as the default way of structuring services.

In practice, it results in domain code that is easier to understand, because it is not cluttered with technical details like database or API mappings. We’ve decoupled different concerns in the code.

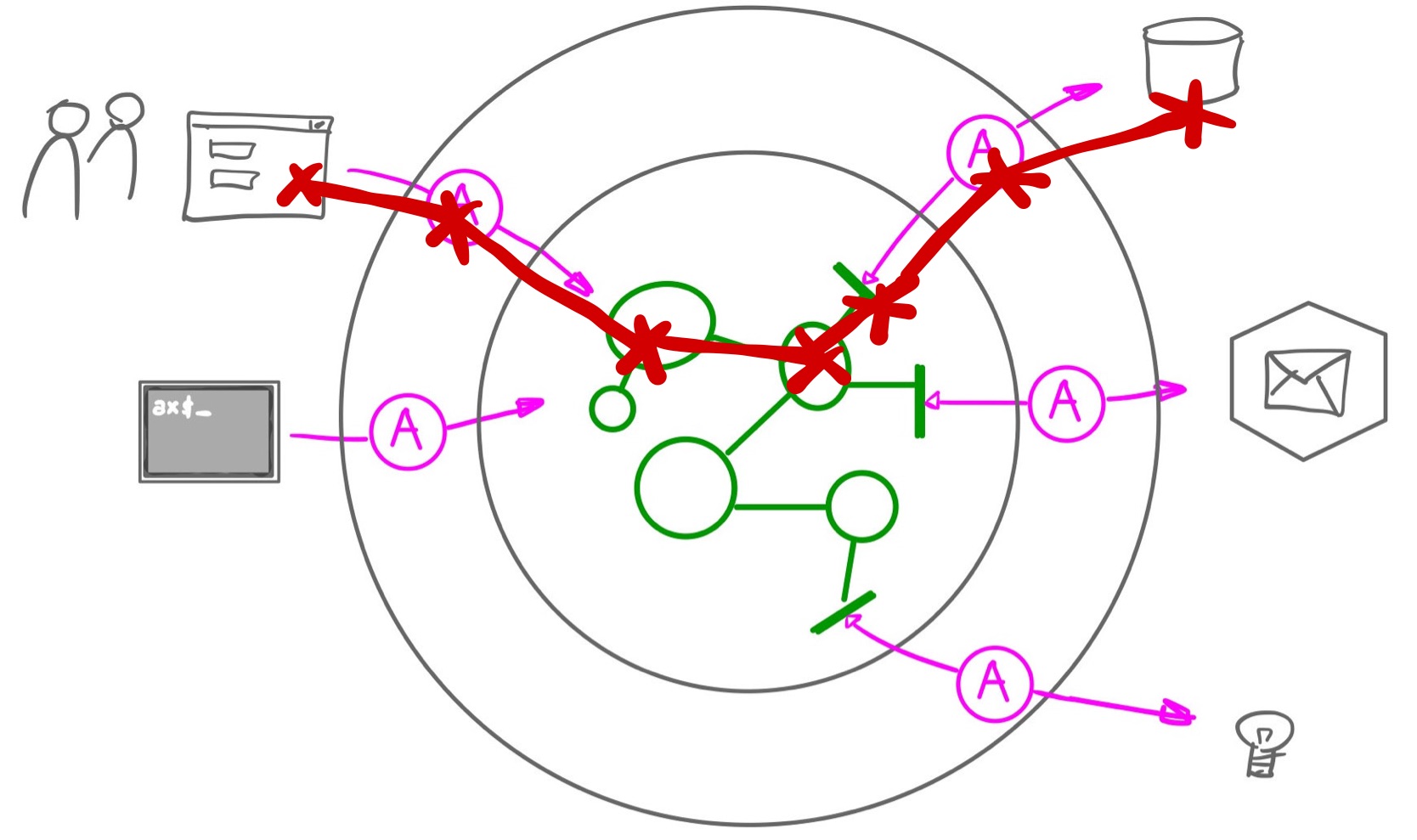

We have noticed something else as well. Sometimes we need to add a new feature and we find ourselves making changes across the component, touching domain logic, the database schema, the database adapter, the API and the API adapter. If this happens, it does not really feel decoupled. It actually looks more like the Shotgun Surgery code smell - having to make many small changes across the code base - or does it?

The coupling & cohesion heuristic we tend to follow is:

If things need to change together, put them close to each other.

So should we put parts of the API, the database mapping and the domain logic closely together because they sometimes change together? It depends…

Different sources of change

It turns out there are multiple sources of change, each having a different impact and each having its own rate of change:

- APIs and database schemas tend to be more stable - especially if other services or external parties depend on our APIs or if substantial amounts of data need to be migrated when the schema changes.

- Frameworks and libraries evolve at their own pace, usually at a slower pace. Once in a while we need to deal with impactful major version upgrades.

- Domain logic has its own pace of changes. We want to be able to refactor and evolve the domain model as we gain new insights.

Applying Hexagonal Architecture means isolating the API, the database and the domain. The trade-off we make is accepting that some (feature) changes will cross the different parts. Hexagonal Architecture optimizes for parts that change at different rates: we are organizing for shearing layers of change - allowing different rates of change with limited friction.

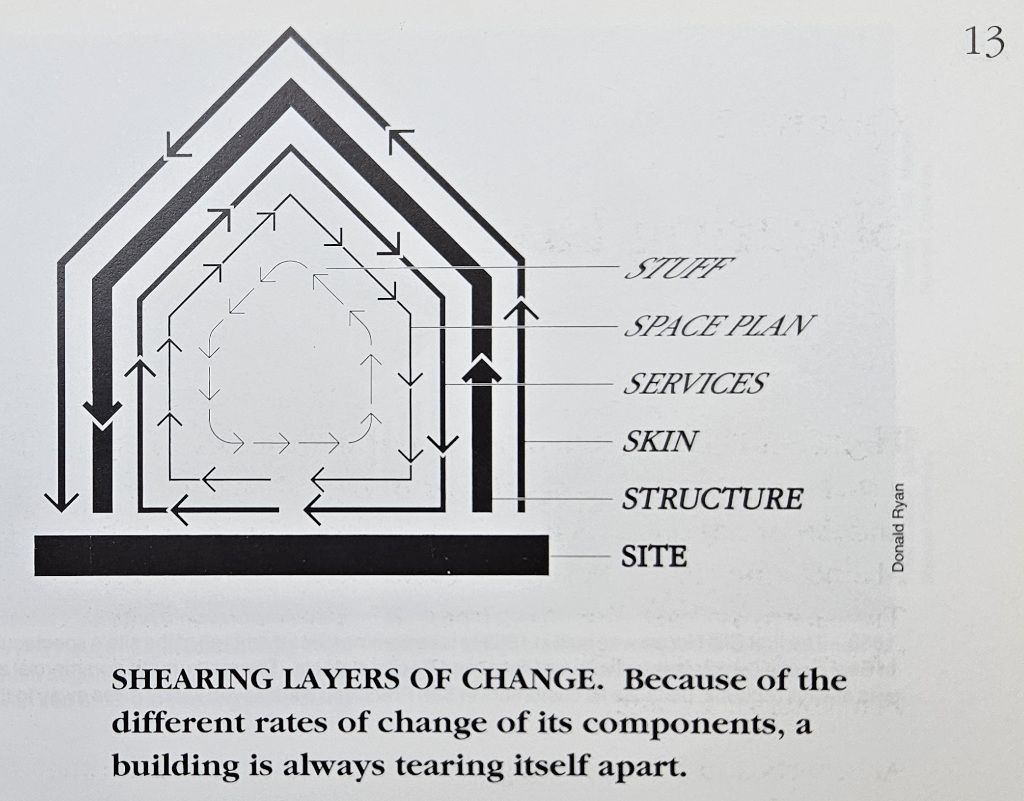

Shearing Layers of change come from (building) architecture and provides a useful perspective on organizing code based on the stability or volatility of its parts.

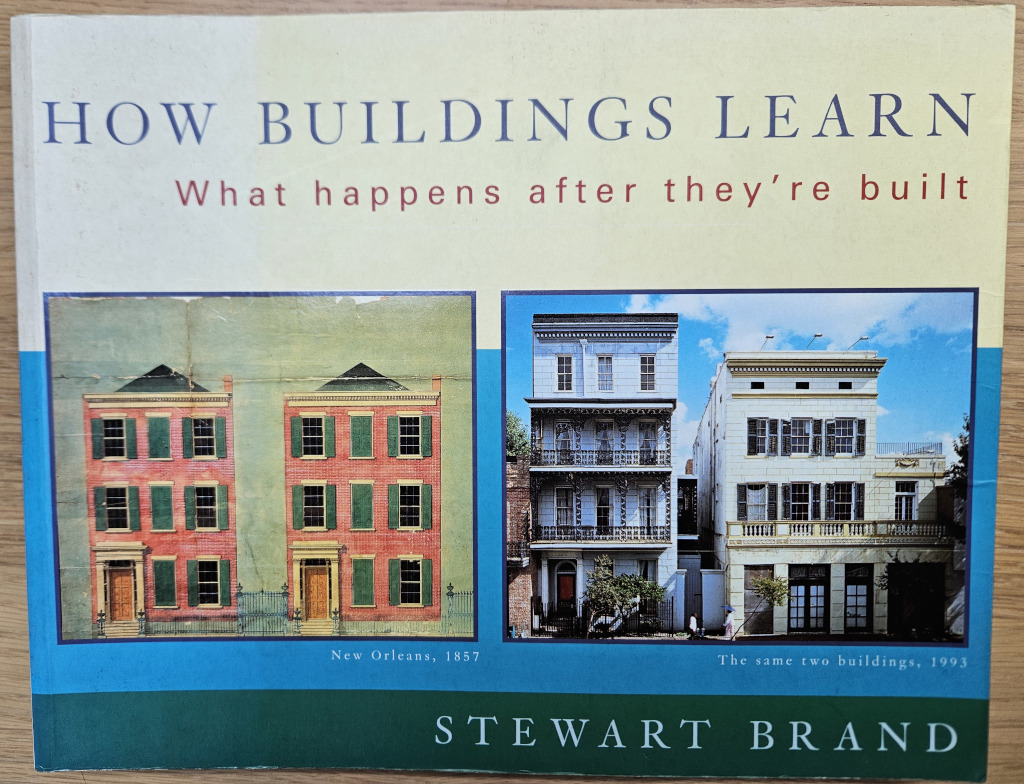

The concept was coined by the architect Frank Duffy, and it was elaborated in the wonderful book How Buildings Learn by Stewart Brand.

Buildings have different layers that change at different rates. The building site is quite stable and often survives a building, the structure is expensive to change so it only changes once in a while. Services like heating wear out, and change every 7-15 years, while stuff (chairs, tables, etc) moves around frequently.

Layers should allow for other layers to change at their own rate.

Hexagonal Architecture optimizes for parts that have different rates of change and it allows the parts to evolve with limited friction

Making trade-offs

Deciding what to put close together and what to separate for facilitating different rates of change involves making trade-offs. Optimizing for each part to evolve at its own pace comes at the cost of new features needing a series of (small) changes.

We are usually willing to pay this price, because it enables us to be much more in control of changes:

- Framework and library updates affect a much smaller part of our system, reducing risks.

- We can more freely refactor domain logic to reflect our current understanding, without continuously needing to migrate data.

- If a feature requires changes across the component, we can do these changes in baby steps, with working software at any point in time. If we think a bit about the ordering of the baby steps, we can even deploy each change to production without impact.

Working in baby steps while keeping the code working at all time is key here. Mechanisms like dependency inversion, domain-oriented interfaces, the ability to test different concerns independently using domain logic tests, adapter integration tests, and component end-to-end tests help a lot.

Hexagonal Architecture and (de)coupling

Hexagonal Architecture separates concerns that have different rates of change. APIs, adapters, databases, domain logic are still coupled, but they do not need to change all at the same time. The coupling is made explicit through interfaces and adapters.

The pattern comes with trade-offs: being in control of changes and the ability to do changes in baby steps come at the cost of some changes being more work.

Hexagonal Architecture was introduced over 30 years ago. There is a more recent insight that rather than creating a single big hexagon for a component or application, we’d rather split the component into smaller, more focused hexagons, to reduce complexity and impact of changes, but this is worth a post of its own.

References

- We have written a series of posts about Hexagonal Architecture

- How Buildings Learn - What happens after they’re built by Stewart Brand; there is also a BBC series of 6 episodes

- Paul Dyson wrote three posts about Shearing Layers in software delivery

- Mark Dalgarno explores Shearing Layers in Shearing layers in Organisational Transformation — half an idea

- Chad Fowler is writing a series of posts on regenerative software, using the idea of Shearing Layers (or pace layering as it is called in his posts)