Coupling and cohesion are old ideas, but they are still relevant today - vintage concepts that have aged well. Recent posts by Martin Dilger and Eberhard Wolff triggered us to reflect on these concepts and explore a bit based on things we have seen in practice.

Coupling and cohesion

Coupling and cohesion are vintage concepts from the late 60s, introduced by Larry Constantine as part of Structured Design. These concepts are independent of programming paradigm or approach - whether it is procedural, OO, functional, low code. Different paradigms and languages do offer different constructs to manage coupling and cohesion.

So what do we mean by coupling? We like the idea of connascence, which was coined by Meilir Page-Jones in his work on object-oriented design. He introduced this term based on the insight that coupling and cohesion are highly related - you could say are two sides of the same coin.

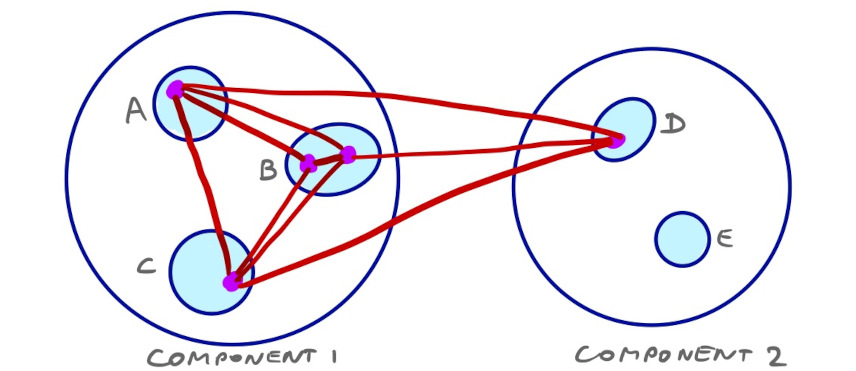

Two software components are connascent (coupled) if:

a change in one would require the other to be modified to maintain the overall correctness of the system

or

for some change, both would be required to change to maintain the overall correctness of the system

Roughly speaking, we want to put things that change together close to each other in a component or module, and separate things that change independently. In this way our components/modules become highly cohesive (closely coupled) while their dependencies with other parts are loosely coupled.

Coupling is not binary. There are different dimensions to coupling and it comes in degrees. The connascence model from Meilir Page-Jones introduces three dimensions, which helps to make conscious decisions on how and when to decouple. We will share more on connascence in a future blog post.

Coupling in context

We often suffer from existing coupling, especially if it is implicit or not-obvious. So we should try to decouple as much as possible in code we write and maintain? We cannot just “decouple everything”. Coupling is to some degree essential to make software work.

Without coupling, we don’t have working software.

The above definition of coupling mentions change. Coupling can be troublesome but only for things that change. If a module is very stable, we will not be affected much by any coupling it has.

So coupling is related to change and rates of change for different parts of our systems. Knowing the volatility or stability of the different parts can help to decide what to decouple. Changes come from the business domains, like changes in functionality, scale, performance, but also from technology, like major framework updates or libraries going unsupported. Although we know change will happen, anticipating specific changes is hard. Over time we usually see what parts become more stable.

It is not about just decoupling everything, but about making architecture and design decisions that help us manage coupling in our context. Some examples:

- make more volatile modules depend on more stable modules and not the other way around;

- make interfaces between modules small and focused, so that consuming modules are not sensitive to changes they don’t care about;

- wrap external dependencies, including frameworks and libraries, in (thin) adapters with your desired interface, to stop framework changes rippling through your systems;

- apply Hexagonal Architecture, to manage coupling between domain models, data models and interfaces to other modules and parties in a highly controlled way;

- apply shearing layers of change (or pace layering) - something worth a blog post of its own.

Look ma no coupling!

We see developers often claiming that they have decoupled two parts. We already mentioned coupling is not binary. So there is some nuance to claims like that.

Martin Dilger recently wrote a post I Still Feel the Urge to Reuse Code (Even Though I Know It’s Wrong), which is a good read on managing coupling.

Let’s take a look at the example in Martin’s post: he describes that a module needs data from another module. Instead of sharing the table (which would introduce strong coupling between the modules), he decided to let the module have its own copy of the data. The copy only contains the attributes that are used by the module: id and title.

This reduces the ‘exposure’ of one module to the other and makes the interface between them small and explicit - only the id and title attributes. This reduces accidental coupling.

Why would accidental coupling be a problem? The module is not actually using the other data right?

Well, when we change the source module, it is often not obvious how much coupling there is. We need to inspect other modules to find out if and how these are coupled, which increases the effort and risk of the change.

Giving a dependent module its own copy of the data also makes the module less dependent on the availability of the source module.

The example also shows that such a decoupling move involves making trade-offs. To keeping a separate copy of the data, you needs a synchronisation mechanism and the data is eventually consistent. This is not good or bad, but it is important to keep these trade-offs in mind and make deliberate decisions about them.

If we’re nitpicky, we could say the example does not remove coupling, but reduces it. The dependent module still depends on the id and title attributes. If these would change, the module should be updated as well. However, we expect id and title to be pretty stable, so this is low-impact coupling we don’t need to worry about.

Decouple by duplicating code?

We sometimes notice some backlash against heuristics like Once and Only Once and Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY), which focus on removing duplication. Removing duplication by introducing some abstraction would create inconvenient coupling - an entangled abstraction that has multiple reasons to change. The counter-proposal is to keep code duplicated so that the ‘duplicates’ can change independently.

This looks like a misinterpretation of the heuristics (or maybe seeing them as hard rules rather than heuristics) combined with prematurely introducing abstractions.

Duplicate code is often a hint there might be an abstraction missing. If we create an abstraction but it turns out we need to change it for different reasons, we probably have entangled different concerns that should not be together. Think of the Single Responsibility Principle - a class or module should have only one reason to change.

If we decide to keep the duplicates and it turns out they change independently, then they are by definition not coupled (using the definition above).

We think considering “what changes together” is more helpful here than focusing on removing literal duplication.

Event based architecture = decoupling?

Another form of decoupling of services we often hear mentioned, is replacing a direct, synchronous call between services by an asynchronous event bus, making them “decoupled”. This does not come for free, but is a trade-off (as always).

Again, decoupling is not binary, but a multi-dimensional scale. Some aspects of coupling are indeed reduced or removed:

- coupling in time;

- the availability of the dependent service does not depend on the other’s availability.

There are still other forms of coupling that remain:

- Dependence on the event format - events are in fact a public API of the producing service, just like a REST API. This form of coupling is well-manageable, e.g. through contact testing, API versioning, API deprecation agreements.

- Dependence on event semantics - how should the events be interpreted? This coupling is more subtle and can lead to duplicated, coupled logic in both services. If the producing logic source changes, you will probably need to update the consuming service as well.

Can we reduce the semantics coupling, e.g. by sending thick events that contain full objects? This increases the interface surface and makes the consuming service dependent on a broader set of data. This can introduce accidental coupling if not all the data is used.

Deliberate (de)coupling

We might sound somewhat critical of decoupling attempts, but we’re not saying decoupling does not work or using events is a bad idea. We find it important to realize what forms of coupling we try to reduce, what coupling remains, how are we going to manage that coupling, and what trade-offs are we willing to make in the process.

Further reading

- I Still Feel the Urge to Reuse Code (Even Though I Know It’s Wrong) by Martin Dilger

- Another good read from this year is Cohesion, Modules, and Hierarchies by Eberhard Wolff

- Meilir Page-Jones, Fundamentals of OO Design in UML (1999)

- Meilir Page-Jones, Comparing Techniques by Means of Encapsulation and Connascence, in Communications of the ACM Sept 1992

- Jim Weirich, The Grand Unified Theory of Software Design, at the Acts as Conference 2009

- Connascence.io

- Vlad Khononov wrote a book on Balancing Coupling in Software Design. We haven’t read it yet, but it’s on our list.

Photo “brown rope on blue wooden table” © 2020 by Dan Dennis on Unsplash